Baruch Toledano from SimilarWeb delivered a talk that pulled back the curtain on how large-scale SEO platforms actually work. Not the features you see in the UI—the engineering decisions that make those features possible and trustworthy.

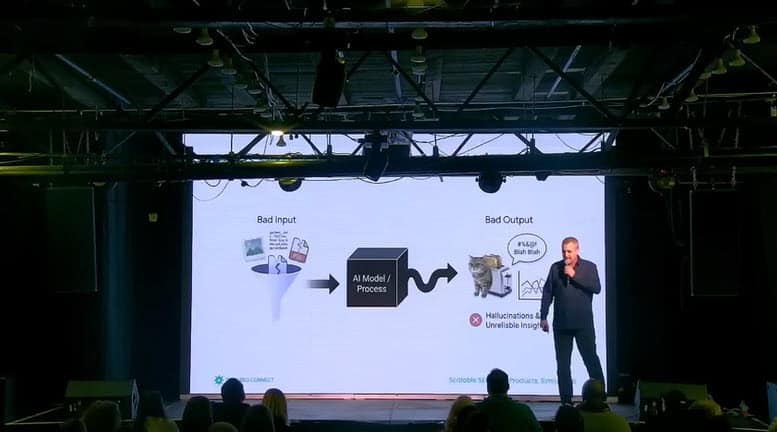

His core message: in 2025, building trust in data has become much harder. The pace of AI capability is outrunning adoption. The amount of data we need to process is far greater. And LLMs, like any system, are only as good as what they’re trained on. “Garbage in, garbage out” now has a new friend: hallucination.

What followed was a masterclass in triangulation, cost optimization, and the unglamorous work of making data reliable at scale.

The Triangulation Principle

Toledano opened with a reality check about first-party data. Even GA and GSC don’t align perfectly. SimilarWeb plots the ratio between GA-reported search traffic and GSC clicks—in an ideal world, they’d match. They don’t.

“There is an absolute ratio that we have been modeling,” he said. They use this to inform the differences between keyword clicks and site traffic. The relationship is reliable enough to build on, but it requires constant validation.

This led to his central principle: triangulation. It’s not enough to detect a change—you have to validate it across multiple data sources. You can’t rely on bias from a single panel member. You can’t trust a model that hasn’t been validated against real-world behavior.

“One thing is guaranteed: there will be change. We just don’t know when.” So the systems have to adapt, constantly, and validate that adaptation against ground truth.

Zero-Click Curves and Real-Time Adaptation

Toledano walked through how SimilarWeb handles zero-click estimation. Every SERP feature has what they call a “zero-click curve”—a marginal contribution to whether users click through or get their answer on the SERP itself.

Each SERP item’s contribution is constantly changing based on order and context. They triangulate this against actual user behavior from their panel—what keywords people search, what URLs they visit. This creates a keyword-to-URL ratio that adapts in near real-time.

“A lot of thinking goes behind this,” he said. “And it’s got to update itself close to real-time because Google constantly changes.” Then they validate against GA and GSC data from actual sites. Multiple layers of verification.

LLM Cost Optimization: The Three-Step Approach

The most technical portion of the talk covered how SimilarWeb uses LLMs cost-effectively. “Working with LLMs can become super expensive very, very quickly,” Toledano said. “The art for us is how do we do it in a cheap way while maintaining our principles.”

He walked through a concrete example: classifying pages into “lines of business” so clients like Carter’s can benchmark against true competitors (not all of Walmart, just Walmart’s kids clothing). This requires processing about 100 million pages daily.

Step 1: Test Feasibility with the Best Model

First, they test whether the strongest available LLM can even solve the problem. “Is LLM really the right answer? Because it may not be.” If the best model can do it, you have a baseline for what truth looks like. If it can’t, you might need a traditional code approach instead.

In this case, the top-tier LLM achieved great accuracy—but the cost was prohibitive for 100 million daily pages.

Step 2: Explore Cheaper Alternatives

For classification tasks, you don’t always need full language understanding. They tried embedding-based approaches: create embeddings for URLs, create embeddings for business categories, use cosine similarity to find the closest match.

“Cheap, easy, fairly quick, doesn’t cost much.” The accuracy was good but not perfect—which led to step three.

Step 3: Distillation and Fine-Tuning

This is where it got technical. They used a teacher-student approach: the strong LLM (teacher) trains a smaller, controllable model (student). The technique is called LoRA—Low-Rank Adaptation—which injects trainable weights into a small language model.

They train these weights using a triplet loss function: make “Apple iPhone 16” closer to “phones” and further from “shoes” in embedding space. Show enough examples, and the student learns to generate URL embeddings that classify accurately.

The key insight: “Distill the process to the places where you need to optimize. Think like engineers—what are the exact places I absolutely have to optimize?”

Brand Extraction: Prompt Engineering at Scale

Toledano’s second example was brand detection in AI Overviews. The problem: 33% of search queries now show AI Overviews. That’s 100+ million AIO paragraphs to process. At roughly 1,000 tokens per AIO, that’s 100 billion tokens just to extract brands—prohibitively expensive.

They started with the strongest LLM, which performed excellently. It correctly identified that “Pink Lady” was the only brand in a list of apple varieties—the others were just varieties, not brands. Hard to break.

Then they tested cheaper models with the same prompt. The problem: the “smart student” LLM gave more than asked—brands plus models, when they only wanted brands.

The solution was iterative prompt optimization. They used Gemini to improve prompts for the cheaper model: “Improve this prompt for this model to achieve these results. Here’s what it failed on. Here’s what I want.” Repeat until accuracy matches, then evaluate cost. If still too expensive, downgrade further and repeat.

Key tactics for prompt engineering with cheaper models: be more specific (which costs more tokens, so there’s a balance), use few-shot examples (“isolate parent brand—if product contains ‘Adobe Acrobat,’ extract only ‘Adobe'”), and specify exact output format to prevent the model from adding unwanted information.

The result: they achieved acceptable accuracy using a model 12x cheaper than the original.

Clickstream as Compass

Toledano closed with clickstream data, which he called “your best view to what’s happening in reality.” At both micro and macro levels, clickstream reveals which AI models are actually being adopted (regardless of what headlines say), how interaction modalities are changing (uploads, file attachments), and where conversions actually happen.

The challenge is representation. An ideal panel would perfectly represent the population—multiply by 10 and you’d have ground truth. Reality is messier: some interests are over-represented, others under-represented.

SimilarWeb addresses this with weighted contribution by topic, following users along their entire path. The principles of triangulation and validation apply here too—no single data source tells the whole story.

My Takeaways

Toledano’s talk was the most infrastructure-focused of the conference. While most speakers addressed what to do, he addressed how the tools we rely on actually work—and what principles should guide building our own.

What I’m taking away:

1. Triangulate everything. No single data source is trustworthy alone. Validate across multiple sources, including real user behavior.

2. Before using LLMs, ask if you need them. Test feasibility with the best model first. If it can’t solve the problem, LLM might not be the answer. If it can, you have a truth baseline—but you probably can’t afford it at scale.

3. Distill to the optimization points. Think like an engineer: what are the exact places that need optimization? Often you can use embeddings and simple classifiers instead of full language models.

4. Cheaper models need better prompts. There’s a relationship between model quality and prompt specificity. Weaker models need more explicit instructions—which costs tokens. Find the balance.

5. Iterate prompt optimization systematically. Use strong LLMs to improve prompts for weaker LLMs. Test, evaluate, adjust, repeat until cost and accuracy align.

6. Clickstream reveals adoption reality. Headlines say one thing; user behavior says another. Clickstream data shows which AI tools people actually use and how.

This talk was a reminder that behind every metric in our SEO tools, there’s engineering decisions about cost, accuracy, and validation. Understanding those trade-offs makes us better consumers of the data—and better builders when we create our own systems.