The rendering process that search engines and AI crawlers use to understand your content involves far more than simply executing JavaScript. Viewport dimensions, computed styles, and layout positioning all influence how crawlers interpret your pages—and specific implementation patterns can cause serious mismatches between what users see and what crawlers index.

The Current State of AI Crawler Rendering

Research conducted with Vercel last year showed that AI crawlers—excluding full browser automated AI agents—weren’t rendering much content. Updated testing this week reveals that landscape is changing. Several AI bots are now capable of full browser rendering, though this doesn’t mean they render 100% of the time. The capability exists; the frequency varies.

New applications like Atlas and Comet introduce additional complexity. When you use Atlas or Comet to view pages, that rendered content becomes available in your chat history even after you close the application. Per ChatGPT Atlas’s terms of service, you can even opt in to having your web browsing data used for training. The connection between Atlas and OpenAI’s servers uses QUIC—the foundation of HTTP/3—making data transfer extremely fast.

It’s worth remembering that crawling isn’t the only source of AI training data. But understanding how rendering works—and where it fails—remains critical for both traditional search and AI visibility.

Understanding the Rendering Output

The rendering process produces three main outputs: the DOM tree (the objects on the page—text, elements, content), the computed style (the styling applied to that content), and the layout tree (the position and dimensions of elements on the page). The SEO industry has largely focused on the DOM tree while underutilizing computed style and layout information.

We’ve discussed “above the fold” content for years, yet relatively little work has been done publicly to leverage layout positioning data. This represents a missed opportunity. Strong platforms are built on strong foundations, and every detail matters in this cumulative game.

Google’s Viewport Expansion Technique

When Google renders a page, they start with one of two viewport configurations—desktop (approximately 1024×768) or mobile (approximately 411×731). But after the initial page load, Google checks how tall the page actually is and resizes the viewport to match that height. If your page is 10,000 pixels tall, Google expands its viewport to 10,000 pixels.

Why? To capture lazy-loaded content. When the viewport matches the full page height, lazy-loaded elements that would normally require scrolling suddenly fall within the viewport and begin loading. Google ends up with a more complete rendering.

Two important caveats: the viewport only expands if the page is taller than the initial viewport, and the viewport resizes only once—no infinite expansion loops. This technique isn’t standard web behavior. Developers don’t typically expect users to have viewports 10,000 pixels tall. This disconnect creates edge cases that can seriously break your content.

Edge Case Problems

When rendering goes wrong, you face two categories of problems: content mismatches (the crawler sees more or less content than intended) and value mismatches (content has different positioning or importance than intended).

Lazy Loading Implementation

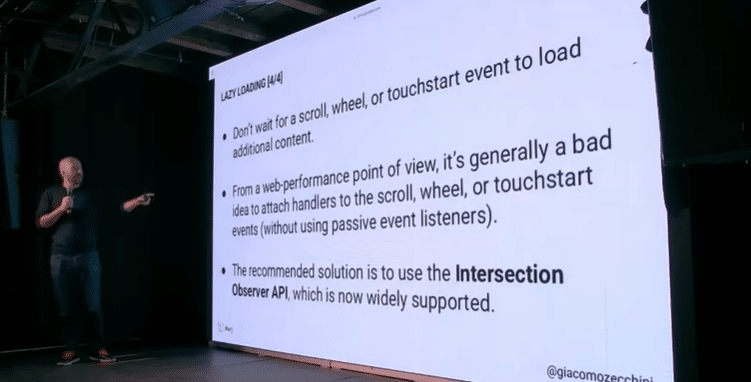

The most common edge case involves lazy loading implementations that rely on user actions. Bots don’t scroll, click, or interact. If your lazy loading triggers on scroll events or click handlers, that content may never load for crawlers. Even worse, action-based lazy loading hurts web performance if you’re not using passive listeners. The solution: use the Intersection Observer API, which triggers based on element visibility within the viewport—exactly what Google’s viewport expansion technique activates.

CSS Before and After Pseudo-Elements

The ::before and ::after pseudo-elements are useful for cosmetic additions—quotation marks, decorative elements. But content added through these pseudo-elements isn’t part of the DOM tree and won’t be indexed. If that content changes the meaning of surrounding text or provides important context, you have a problem. Use pseudo-elements for decoration only, never for meaningful content.

Heading Visual Hierarchy

Google’s Search Off the Record podcast revealed that they use the styling of HTML heading tags to determine relative importance. A tiny H1 stuffed with keywords at the top of your page may carry less weight than a prominently styled H2. Google examines the computed style—font size, visual prominence—not just the HTML tag hierarchy. When possible, respect visual semantics. When that’s not possible, understand that your H1 might not be treated as your most important heading.

Display None vs. Visibility Hidden

Elements with display:none exist in the DOM tree but not in the render tree—they have no position and no dimension. If search engines use element positioning to assess content prominence, display:none content may be devalued or ignored entirely. Visibility:hidden provides an alternative: the element retains its position and dimensions, it’s simply not shown. If you need to hide content while preserving its structural relationship to the page, visibility:hidden is the safer choice.

Infinite Scrolling and the History API

Many sites implement infinite scrolling by appending content as users scroll and using the History API to update the URL. Article one loads on /article-1, you scroll, article two appends, the URL changes to /article-2. This creates a problem when combined with viewport expansion.

Google starts on /article-1 and expands the viewport. Article two loads because it’s now within the expanded viewport, but the URL remains /article-1. Result: article two’s content gets associated with article one’s URL. Some implementations replace earlier content with later content as you scroll. Factor in viewport expansion, and you might have article two’s content indexed under article one’s URL entirely.

The solution: detect the crawler’s user agent and disable infinite scrolling for bots. You can implement this server-side (don’t include the infinite loading code) or client-side (block the function when the user agent matches known crawlers).

The Viewport Height Trap

Full-screen hero elements that use viewport height units (100vh) to create dramatic visual experiences become problematic with viewport expansion. If Google expands to a 100,000-pixel viewport and your hero image uses 100vh, that image becomes 100,000 pixels tall. All your actual content gets pushed far down the page.

If Google uses above-the-fold positioning to assess content importance, your meaningful content now appears to be buried deep in the page—not prominent at all. The fix is simple: set a max-height on full-screen elements. 1000 pixels is reasonable. The visual effect remains intact for users while preventing the viewport expansion trap.

This problem compounds with lazy loading. If your content uses lazy loading with intersection thresholds, and a viewport-height element pushes those thresholds far down the page, the lazy-loaded content may never trigger. Again, max-height solves both issues.

AI Agents and Non-Deterministic Behavior

Full AI agents with browser capabilities can render any website. But these agents are non-deterministic. A vague instruction like “get me the full content of this page” might result in the agent simply not scrolling, returning only partial content. The predictable rendering behavior we expect from search engine bots doesn’t apply to AI agents that make their own decisions about how to interact with pages.

Practical Applications of Layout Data

Layout information has applications beyond diagnosing rendering problems. You can analyze above-the-fold content composition systematically. One company used layout comparison to assess whether similar brand presentations across their portfolio were diminishing perceived differentiation—and affecting conversion rates.

During domain migrations, comparing layout data between old and new domains can reveal rendering breakages—perhaps a content security policy is blocking JavaScript, or a beacon isn’t firing. Layout data also makes intrusive interstitial detection straightforward: if a large element covers the entire visible area, you have a problem.

Key Takeaways

Not all crawlers render web pages, and even those that do may miss content due to edge cases in your implementation. Google’s viewport expansion technique—while useful for capturing lazy-loaded content—is not a standard web behavior and can break sites in unexpected ways.

Use Intersection Observer API for lazy loading, not scroll or click events. Avoid meaningful content in CSS pseudo-elements. Understand that heading importance is determined by visual styling, not just HTML tags. Consider visibility:hidden over display:none when positioning matters. Disable infinite scrolling for crawlers. Always set max-height on viewport-height elements.

Most importantly, start using layout information and computed styles in your day-to-day work. The DOM tree is only part of the story. Position, dimension, and visual hierarchy all influence how search engines and AI systems understand your content.